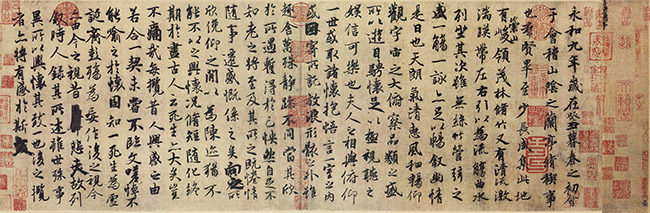

A Tang Dynasty copy of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, written in fourth century by the "Sage of Calligraphy," Wang Xizhi.

Of all those who strive to leave their mark on history, perhaps writers are some of our clearest messengers. Their thoughts and dreams are indelibly left as ink on paper for centuries to come. From one line of verse we can read the past of a poet’s thoughts, speaking to us through his own words.

More so does this ring true in ancient China, where the act of writing a word was itself an art form. Everyone—from the humblest student to the mighty emperor—found rapture in the placement of characters known as calligraphy.

Ironically, China’s own “Sage of Calligraphy” has little of his original work existing under his name. Wang Xizhi (301-361 A.D.) was a contemporary of the Jin Dynasty whose writings were revered and copied in a society where imitation was truly the highest form of flattery. Today, reproductions of his work are almost all that remain and serve as a tantalizing glimpse into the handwriting of a man who held a nation spellbound.

His most famous piece was Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, a 324-word masterpiece written as a celebration of an idyllic afternoon.

Putting aside backstory for a moment, the words of the Preface paint a picture in themselves: as “airy as a cloud, yet with strength to startle dragons;” taking “flight beyond heavenly gates;” like “tigers lying in wait” and as guards before a “phoenix pavilion.”

This preface and calligraphic masterpiece from seventeen hundred years ago is the inspiration for Shen Yun’s 2016 dance, Poets of the Orchid Pavilion.

The Poet

A descendent from a family of renowned writers, Wang began practicing his script at age seven with a female calligrapher named Wei Shuo. Five years later, his teacher was certain that Wang’s talent would soon surpass her own. Wang was an enthusiastic learner, often forgetting to eat in favor of writing. He owned many brushes, ink stones, paper and ink sticks, which were scattered all about his study, courtyard, and around the house for ease of practicing. A story claims that Wang would clean his brushes outdoors in a little pond—so often that he turned the water to ink.

Wang, who was known for his candid nature and cared little for fame, soon became renowned nonetheless. One day, for example, Wang saw a Taoist herding a flock of geese. Wang wanted to buy them and asked for the price. The Taoist replied that they were not for sale, but that he would gladly trade them in exchange for a hand-copied excerpt from the sacred Dao De Jing. The calligrapher traded in his handwriting and went home 10 geese richer.

What was unique about Wang was his mastery of multiple calligraphy styles: the standard and uniform regular script, the loose and flowing running script, and the blurred and stylized cursive script. Most people spent years perfecting only one style, but he could handle three with ease, and contributed greatly to the maturation of further calligraphic styles.

Wang’s five sons carried on his legacy in the structure, strength, and shape of their writing, each becoming calligraphers in their own right. Of all his children, the youngest, Wang Xianzhi, achieved the greatest acclaim. During his lifetime, this son’s fame even eclipsed that of his father—but later scholars returned the title of “greatest” to Wang senior.

The Poem

On the third day of the third lunar month of 353, Wang Xizhi invited a group of family and friends to his Orchid Pavilion for the Spring Purification Festival. Water and orchids were said to ward away the evil vapors of winter on this day, bringing good fortune in its place. The pavilion was surrounded on all sides by fresh bamboo and lofty mountains, and overlooked a winding stream. The day was sunny but cool—a refreshing breeze drifted through the air, and many of the guests settled themselves by the banks of the water.

Servants sent floating cups of wine flowing downstream, and where they stopped, the nearest guest had to compose a poem on the spot—or drink three cups as penalty. Of the 41 guests, 26 composed a total of 37 poems, inspiring Wang Xizhi to pen his famous Preface. Historical records state Wang used a weasel-whisker brush on cocoon paper.

This same work would be passed down in the Wang family for generations until its last surviving heir—a monk named Zhiyong—gave it to the care of his disciple Biancai. By that time, nearly three hundred years had passed and the Tang Dynasty (618-907) had just established its rule over China. Eventually, the manuscript found its way into the hands of Emperor Tang Taizong, who had previously only seen copies of the original.

More copies of the Preface were traced, written, and even engraved on stone, though legend states that the emperor took the original with him to the tomb.

In subject matter, the Preface is a simple description of the poet’s musings—but written so elegantly, so masterfully that it leaves a heavy impression on the reader. Many words appear in it multiple times: the character 之 (pronounced zhī, meaning “of,” and also part of his name, Wang Xizhi) shows up 20 times alone, but each time is written differently, carrying unique stylistic flavors.

In this work, too, lies an appeal to the present—and the future. A written prediction by the poet states that future generations “will look upon us just as we looked upon the past.” The joys and disappointments of living, the cherished memories of happiness, are but a blink of history’s eyes. But even though time may change, human sentiment will not. It is constant in its inconstancy, full of rhythm and cadence echoed in the Preface’s own handwritten characters.

Wang Xizhi writes, but not for history, and not wholly for himself. Rather, he observes life and shares it with us, his future readers, inviting us to live as he does in the past. The “causes for feelings and mood remain the same,” he says, metaphorically extending his hand to ours.

For a calligraphy sage, he is also a masterfully candid poet.

“Read me and see,” the poet coaxes. “We are not so different, you and I.”